10GENDERPORTRAIT

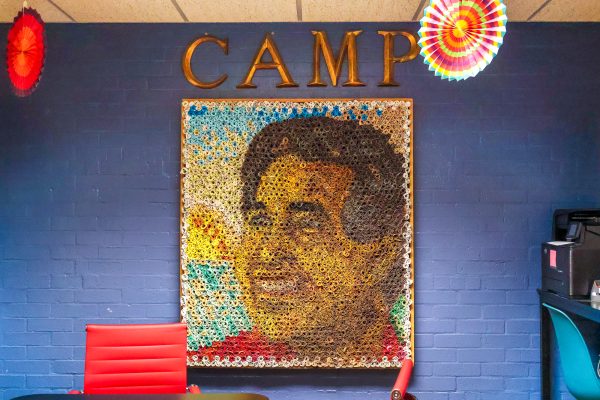

Drew Riley’s “Gender Portraits” art series began as therapy for herself in her journey as a trans woman. As the project took form, she soon realized her motivation was rooted in helping others feel less alone in their journeys.

Last Tuesday, Riley’s series made its way to St. Edward’s with the help of student organization America I Will. Portraits from Riley’s series spread all around the North Reading Room in the Munday Library for observation.

Riley’s portraits are painted with acrylic on canvas with stories in the background or alongside the portrait. The series explores the complexity of gender through of a wide range narratives of people,gathered through interviews she conducts herself. In the final steps, Riley shows the subjects their portraits to allow adjustments. Riley says this constant communication allows her to make sure her role as an artist is defined clearly.

“I try really hard to have their voice be the one that’s carrying through,” Riley said. “I kind of serve as a narrator, but I try to not serve as a speaker.”

In Riley’s experience as a trans woman, she’s learned the best way to reach allies is through others knowing and befriending trans people—which is what she works to convey through portraits connected with stories.

Riley typically paints off a photo; however, in the beginning of the series, Riley used to interview subjects around Austin paired with a photoshoot. As the project expanded, she reached subjects all the way in Canada and Latvia who interviewed over Skype. Many of the smaller canvases come from online questionnaires and photo submissions from the Gender Portraits website. Riley then pulls quotes from the questionnaire and references them on the painting.

When first starting the project, Riley wanted to use the medium to express language from the community that’s often difficult to explain.

“I didn’t want to be either speaking for people that I had no idea what their experiences were like or just speaking for myself only and then having people assume that’s what all trans people are like,” Riley said. “I wanted to have a variety of subjects to basically be a stage for them.”

Riley’s portraits are not limited to trans subjects. She also takes portraits of people who are intersex or have Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Riley also captures those who present their bodies differently and those who are cisgender but use gender presentation as a performance.

“I kind of gives context and a broader conversation so that you’re not just talking about this trans-ness in isolation,” Riley said.

What started as an art series transformed into a sponsored project of the Austin Creative Alliance that gained profit status.

Riley explained the three large portraits sat in the middle of the room are a part of a four-part self-portrait series. The concept centers around the stages of Riley finding herself as a trans woman. The self-portraits were more about the psychological and social concepts that Riley dealt with rather than her physical transformation. The first is called “Adolescence,” the second “Exploration” and the third “Prudence.” The fourth will be called “Covert.”

While reflecting on “Prudence,” Riley said the piece centers around changing perspectives of herself through day-to-day experiences like grocery shopping and being catcalled. Riley sought to understand her position in the workplace as a commanding yet feminine presence—a combination not typically embraced by traditional conceptualizations of femininity.

“Now I’m the bossy bitch and aggressive and navigating those [identities] for the first time,” Riley said.

As Gender Portraits has evolved, Riley recognized the series as a form of therapy—especially through her interactions with trans men.

“All the details were basically flipped,” Riley said. “What they were running from is what I was running towards. And what they were embracing was things that mortified me.”

Seeing the flip of Riley’s experiences emphasized the overarching mission to be at peace with herself; Riley was able to let go of the gnawing question of why she wanted to transition—whether it was struggling with body image, being raised in gender roles or other details that wracked her brain.

“To see it laid out like that reminded me that actually the details were a symptom of my personality and who I wanted to be,” Riley said. “What made me trans was this overall lack of fitting of what was given to me at birth and this broader arc. The rest was just superficial when defining what being transgender means, that’s just what being Drew means.”