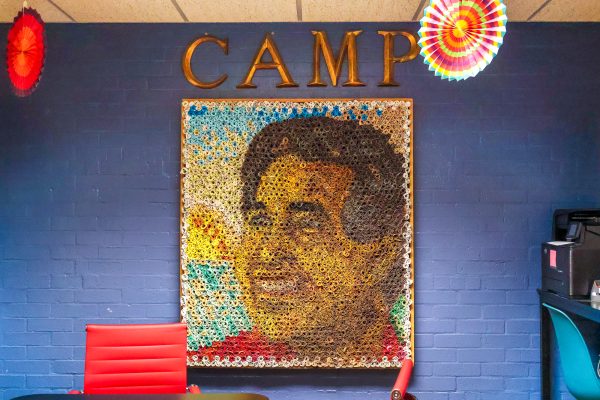

Retiring photo program coordinator reflects on building, changing curriculum

“I love it when people find out you’re retiring and they say, ‘oh well what are you going to do?’ Photocommunications professor and Program Area Coordinator Bill Kennedy said. “That just tickles me. I’m going to do exactly what I’m doing.”

And what exactly is Kennedy doing? Aside from teaching students, Kennedy is a documentary and fine art photographer with a love for inkjet printing.

“When digital began, I fell in love with the idea of making inkjet prints . . . and I was able to then bring that experience back and develop a curriculum and share it in the classroom,” Kennedy said.

When Kennedy built the program in 1981, it was completely analog, and his goal was to develop a program that was unique in its emphasis on literacy.

“Most photo programs are either fine art programs or they’re more trade oriented — like I went to a photojournalism program,” Kennedy said. “We didn’t want that. We wanted to build something that was based around the idea of visual literacy, and that’s been the guiding light philosophically.”

It was not easy to shift the curriculum from analog to digital imaging, but Kennedy’s early passion for the change made it easier. Kennedy had always wanted to be a printmaker, and inkjet printing gave him the opportunity to make prints with ink.

“I got involved very early, and I think that turned out to be fortunate because I climbed the learning curves for myself,” Kennedy said. “And then I was able to build a curriculum that we needed for the photo program when we went from analog into digital.”

As an artist, Kennedy seems to embrace change in general.

“One of the great things about being a photographer, about being an artist in general, is that evolution,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy’s personal work has changed a great deal. Describing it as a “sloping turn, one thing leading to another,” Kennedy has spent the last few years creating abstract images.

The key turning point for this work was when his wife, a painter, introduced him to Tantric painting, which is comprised of Indian art characteristics. Kennedy’s shift from literal to abstract photography was driven by an internal shift in interest — from what an image is to how an image feels.

“The key turning point for me was seeing tantric paintings for the first time and realizing the power of symbol and color in an image,” Kennedy said. “So basically what has happened is I’ve moved away from content and am more interested in the emotive power of form and color.”

Kennedy has always found that his work outside of teaching has helped him guide his students. For example, his work as a commercial photographer led him to teach his students about the business side of photography.

“It has been an interesting process because I’ve just been very lucky that way,” Kennedy said. “I’ve done things outside of my career as a teacher, but almost always they’ve ended up coming back into my teaching, making my teaching better, stronger.”

However, this connection is not direct when it comes to content because of Kennedy’s teaching style.

“I dont like telling students what to photograph,” Kennedy said. “I like raising questions and I like the dialogue that comes from looking at those questions, but I think it’s imperative that each person come to their own definition of what makes a good photograph.”

This combination of freedom and conversation is Kennedy’s greatest accomplishment as a professor.

“I think that my best teaching is more about being able to have an ongoing conversation … helping them understand its a personal journey, and that they have to find their own voice, and that failure is as important as success,” Kennedy said. “So I don’t think you can teach any artform on a formula. I think in the end it’s really about relationships.”