11Psy.

Traditional college students are at the highest risk period for problematic substance use, and many St. Edward’s students will experience the “maturing out phenomenon” by the time they walk out the red front doors at graduation.

Assistant Professor of Psychology Kelly Green describes the maturing out phenomenon as occurring when someone develops problematic substance use patterns but then goes through lifestyle changes that require responsibilities and social roles that lead them to no longer abuse substances.

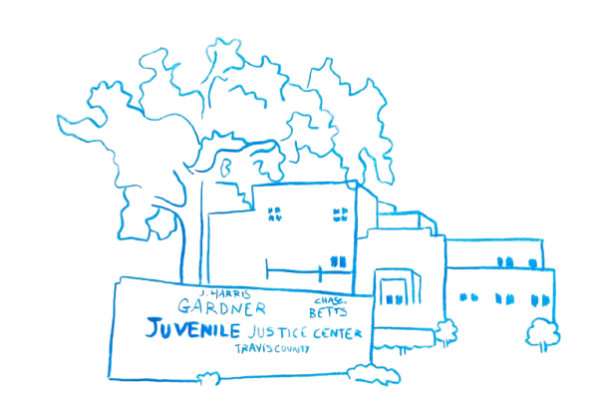

Though people ages of 18 to 25 are at a high risk to abuse substances, others don’t “mature out.”

Anyone with other mental health issues that would benefit from professional treatment faces an issue of breaking past the stigma surrounding mental health. Green said the stigma can be even greater for those struggling with addiction.

“The way we treat addicts doesn’t work…we cut them off their social connections and it’s kind of the opposite of what people need at that point in their life,” Green said. “Unfortunately, it’s really hard to get that message across when you’re really worried and when you’re really angry at some of the things the person is doing.”

Also a clinical psychologist, Green sees not only those struggling with addiction but people trying to cope with having a loved one who abuses substances.

“Sometimes they feel like they don’t have a right to be upset about it,” Green said. “There’s a lot of kind of feeling guilty – like they’re not the ones struggling so why should they be in treatment?”

A way to be helpful for those facing addiction is to provide positive reinforcement, and avoid misuse of clinical terms.

Positive reinforcement could be practiced by someone expressing how much they enjoyed spending time with the other on days they stay sober, and detaching on days they don’t, rather than threatening or punishing the person.

Something everyone can keep in mind, and not just those who know someone struggling with mental health disorders, is to reserve use of certain vocabulary for instances that it’s relevant.

“So we say, ‘oh he’s such a narcissist’ or very ‘anti-social’ or ‘I was feeling very bipolar.’ We use these terms that are clinical terms that mean something very specific, but we misuse them a lot in the common vernacular so that leads to some problems,” Green said.

Another clinical psychologist at St. Edward’s aims to combat the stigma surrounding mental health by thinking of it like any other medical condition rather than a personal weakness.

“If you had a huge migraine, you wouldn’t have any stigma about going to a doctor and getting a prescription for migraine pills, and psychological disorders are the same thing,” said Assistant Professor of Psychology Tomas Yufik. “So, it’s just like getting a pill for a migraine, therapy is kind of like, in the future, will be totally normalized. ‘Yeah i have a migraine or a headache, I’m feeling a little depressed, I’ll just go and get some therapy.’ That’s where it should be.”

Still, it remains uncertain how many people in the St. Edward’s community are dealing with mental health conditions, and whether they are accessing resources available to them.

The annual diversity survey includes a question asking whether or not students, faculty and staff have faced mental health problems in the past year. Green is hopeful that it will help develop new programs or policies for those who are struggling.

“One of the things we don’t get a good sense of is how many students are struggling with mental health problems at the university level,” Green said. “We can get data for that by looking at how many people go to the counseling center, but that doesn’t capture it fully.”