REVIEW: What makes Austin’s rendition of “Hamilton An American Musical” special

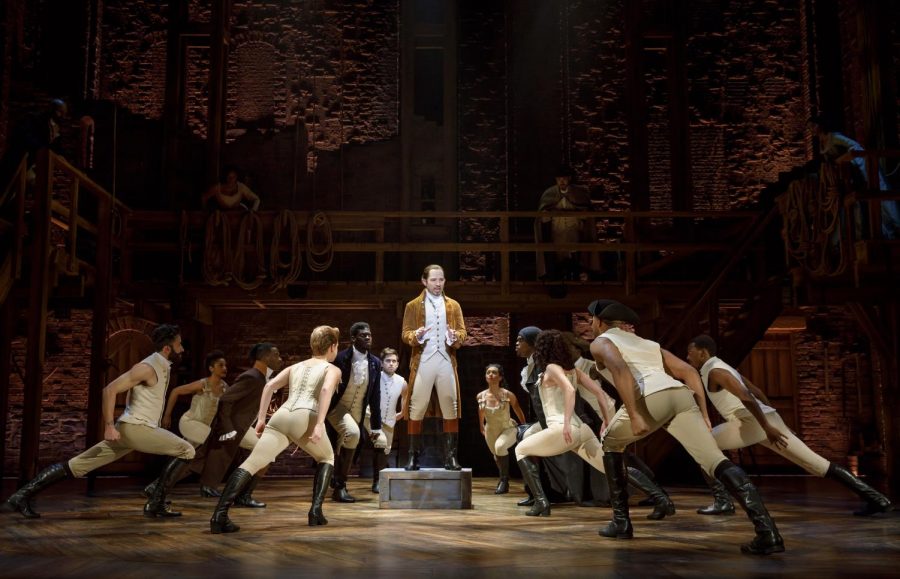

Courtesy of Hamilton National Tour

The company of Hamilton and Joseph Morales performing on stage. The show is currently being performed at Bass Music Hall in Austin.

More than asking what it means to be American, Austin’s rendition of “Hamilton An American Musical” asks what it means to live in this city?

How do I begin to write about the goliath of a musical that is Hamilton, whose reach has run circles around the globe and permeated even the most averse showtune populations?

From its ingenious use of the hip-hop/rap genre as a medium for showtune-esque storytelling, to the way its masterfully complex characters epitomize American values that reach to the core of our mortality to wonder what it is we hope to make of our lives, both personally and as part of a nation, to the furious political relevance it has, especially to immigrants and communities of color, Hamilton has, in short, been talked about a lot. What can you add to a global conversation that doesn’t sound like an echo?

You listen for what no one else hears, and I heard dissonance.

It wasn’t the music (it was, as expected, phenomenal) and it wasn’t the singing or dancing (I’m still in awe of any song that featured the Schuyler sisters) or even the acting (Joseph Morales’s more drawn out take on Hamilton shows us a thoughtful, mentally hard working side rather than a natural genius). It was Austin. Hamilton and Austin seem, as Lin-Manuel would put it, “diametrically opposed foes.” And I couldn’t stop seeing this stark contrast on stage, in the audience, and throughout the city.

I sat 10 rows from the stage, row J seat 8, with a perfect view of the stage (a child sat in front of me, to my good fortune). The prices of tickets were as intimidating as the musical itself, so it was a strange, fish-out-of-water experience sitting amongst people who could leisurely afford the exorbitant price of a seat while I had refused to even pay parking (my friend dropped me off).

I would later discover that tickets in my section cost $539.

One of the crowning achievements of this musical has been its ability to move people usually on the margins of society to center stage with both the story it tells and its casting. Where the plot follows Hamilton as a “bastard orphan immigrant” moving from the margins of society into a leading role in shaping the nation’s future, the casting call follows suit perfectly, centering actors of color in leading roles in order to reflect America today.

In the Austin rendition, it means a Korean George Washington (Marcus Choi), a mixed-race Alexander Hamilton (Joseph Morales), and a Black Aaron Burr (Nik Walker), among other amazing and ethnically diverse characters.

I wondered for a moment, where these actors might reside if they lived in Austin. During Choi’s break from invincibility in his vulnerable and resonant rendition of “One Last Time,” I saw him living in North Austin, where a large portion of Austin’s growing Asian-American population reside along with their restaurants and shops. When Morales and Walker sang in harmony about the uncertain future of the nation in “Dear Theodosia,” I saw that same uncertainty and vulnerability as if they were residents of color in Austin’s increasingly gentrified East side.

The racial break down of the city is pretty common knowledge to the locals, but uncommon is an awareness of the intentionality of this segregation. Black and brown communities didn’t just randomly favor the East side, nor did affluent white communities randomly favor the west and downtown. The segregation of Austin resulted from a series of intentionally discriminatory policies, including the 1928 Master Plan that forced minorities into designated areas by restricting their access to public services outside designated zones, and the 1935 New Deal housing programs that would redline the entire east side from receiving government mortgages. These grave inequalities would build a foundation from which, as Austin would continue to grow exponentially, the city’s would additionally grow into the most economically segregated metro area in America.

If Austin were a stage, minorities would be nowhere near front and center. They likely wouldn’t even get through the door.

Within Bass Concert Hall, with actors of color brought center stage while a majority white, affluent audience sat in the offstage outskirts, Hamilton turned Austin upside down for a moment in time.

In the final notes of the musical in “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story,” Morales nudges Erin Clemons, who plays Eliza Hamilton, forward to center stage as she reaches for something in the distance. The stage goes dark. The lights come back up and the cast takes their bows. And I walk back out to the Austin I know.

Art so often serves as a space to imagine what is possible. Theatre enacts that world in ways that we can understand, can be inspired by, can strive towards. If it has done its job well, it inspires more questions than answers.

Plenty of reviews have discussed how this play begs the question what it means to be an American. Its rendition in this city begs a more pointed question: what does it mean to be an American in a still segregated America? And how do we manifest the Hamilton we saw on stage in the Austin we live in?

I am Lilli Hime—English Writing and Rhetoric major and freelance writer at Hilltop Views. This is my senior year at St. Edward's University.

My role...