Each fall semester, St. Edward’s University unites its incoming class with a single, shared reading that fuels seminars, projects and field trips. This year’s common theme, “Home and Shelter,” asks students to look beyond brick and mortar and consider what it truly means to feel safe, secure and a sense of belonging. The Senior Director of Academic Initiatives Emma Woelk has taken a bold step, assigning not one but two books that each illuminate a different facet of the theme.

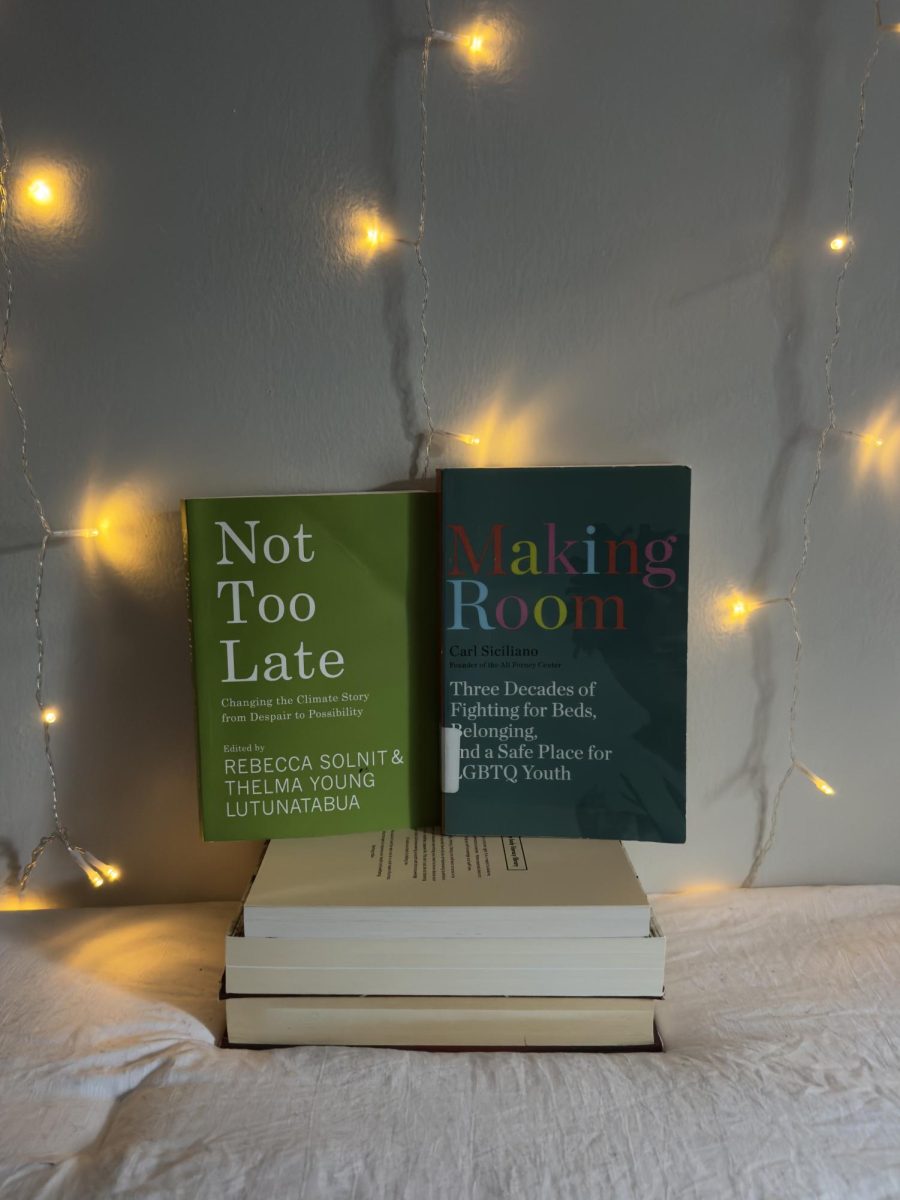

Rebecca Solnit and Thelma Young Lutunatabua’s edited collection, “Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility,” approaches shelter from a planetary perspective. Climate change threatens the literal roofs over millions of heads — rising seas, wildfires and extreme weather already displace families worldwide. Yet, the volume does more than catalog disaster; it reframes the narrative, presenting stories of communities that have turned the tide through renewable energy, urban farms and grassroots activism. By presenting climate action as an act of protecting our shared home, the book urges students to see themselves as stewards of a world that belongs to everyone.

In contrast, Carl Siciliano’s memoir, “Making Room: Three Decades of Fighting for Beds, Belonging, and a Safe Space for LGBTQ Youth,” dives into the personal and social dimensions of shelter. Siciliano chronicles his tireless advocacy for LGBTQ+ youth who are often left homeless or forced out of family homes simply because of who they are. The narrative brings to light the stark reality that for many, “home” is not just a structure but a feeling of acceptance and safety — a place where identity is affirmed rather than denied.

I chose to read “Not Too Late,” and the experience felt like a mental‑training manual for optimism. Rather than dwelling on doom, the editors curate success stories that demonstrate how ordinary people can make extraordinary change. One chapter details a Detroit neighborhood that transformed vacant lots into thriving urban farms, providing fresh food and a sense of community. Another follows a small Icelandic town that built a micro‑grid powered entirely by geothermal energy, cutting its carbon footprint while lowering electricity costs for residents. Each story ends with clear, actionable steps, turning abstract climate data into personal projects that a freshman can realistically undertake. The book’s hopeful tone kept me engaged and motivated to join campus sustainability initiatives, reinforcing the idea that protecting our planetary shelter is not a distant, impossible goal but a daily responsibility we can all share.

To capture the other side of the theme, I spoke with freshman Kate Gomez, who selected Siciliano’s memoir for her reading. “This book really opened my eyes,” she said, her voice tinged with the empathy the stories evoked. “I never realized how many LGBTQ youth are homeless just because of who they are.” She went on to describe the emotional impact of the narratives: “It’s heartbreaking, but also hopeful — you see how one person’s work can actually change lives.” When asked how the book connects to the common theme, Gomez added, “It shows that home isn’t just a place. It’s where you feel safe, accepted, and seen.” Her reflections underscore the emotional dimension of shelter that Siciliano so powerfully illustrates, reminding us that a roof over one’s head means little without the sense of belonging that makes a house feel like a home.

Assigning two books rather than one brings several advantages to the freshman experience. First, it gives students a choice, allowing each reader to gravitate toward the narrative that resonates most with their personal interests — whether that’s climate action or social justice. That sense of ownership deepens engagement and makes the reading feel less like an assignment and more like a personal journey. Second, the dual perspective forces students to think intersectionally. In classroom discussions, a conversation about renewable energy often spirals into questions about who benefits most from clean technology, prompting students to consider how climate‑driven displacement disproportionately affects LGBTQ+ youth and other marginalized groups. Finally, the requirement that each seminar group compare notes from both books ensures that no one walks away with only half the story; the curriculum weaves the texts together through joint presentations and cross‑reading assignments.

Professors have built in comparative essays, collaborative projects, and community‑service components that demand students engage with both narratives. In practice, this approach mirrors real‑world problem solving, where issues rarely exist in isolation. By confronting climate change and LGBTQ+ housing insecurity side by side, freshmen learn to recognize the interconnectedness of social challenges and to craft solutions that address multiple layers of need.

The tradition of a common freshman read itself remains a powerful catalyst for community building. When an entire class starts the semester with the same story, a shared vocabulary emerges that makes it easier to form study groups, spark informal debates in the dining hall, and connect personal experiences to larger societal issues. The reading becomes a touchstone for campus resources — students who are inspired by the climate volume may seek out the Sustainability Office, while those moved by Siciliano’s memoir may find support at the OSBIE. In this way, the common theme does more than fill a syllabus; it lights a path toward deeper involvement in campus life.

As we close this semester’s first installment of the “Common Theme” column, the message is clear: protecting our planet and fostering inclusive spaces are not separate endeavors but parts of a single, larger quest for a world where everyone can call a place home. The dual‑book selection for 2025 captures that spirit, offering both the big‑picture urgency of climate stewardship and the intimate, human stories of belonging.

And, as our mascot the Hilltoppers goat might say, “We may climb the steepest peaks, but we always find a safe, welcoming ledge to call home.” With that goat‑ish optimism, let’s keep climbing, protecting, and building spaces where every student feels truly at home.