South Austin contains food deserts, healthy choices scarce

Wayne Holmes walks everywhere he goes in Austin. He walks 45 minutes from his apartment complex near St. Edward’s University to his job at Mrs. P’s Electric Cock, a food truck on South Congress Avenue. He walks 20 minutes to get food from a fast food restaurant or groceries from H-E-B. And then he has to walk back.

Holmes, 21, lives in an area that is labeled as a food desert by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) economic research service. Food deserts are defined as urban neighborhoods and rural towns with limited access to fresh, healthy and affordable food. Instead, they have a higher percentage of fast food restaurants and convenience stores than grocery stores, which severely limits the dietary choices their residents have.

“The walk to get groceries isn’t as physically exerting as the walk back,” Holmes said. “It can be a pain depending on the size of and amount of things I have to buy.”

Holmes doesn’t have a car, and rarely depends on rides from friends to get him where he needs to go. Not having a reliable form of transportation affects what he chooses to eat, simply because buying fast food is cheaper and easier to do without a car.

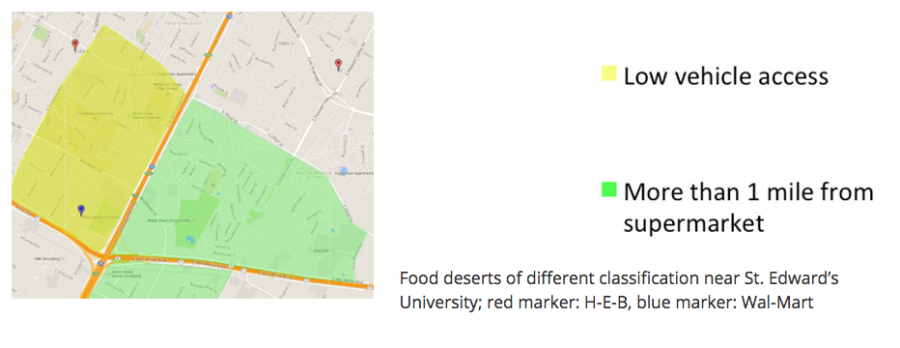

According to the USDA, the urban area surrounding St. Edward’s is considered a food desert because of a lack of vehicle availability, which is a dilemma that many young people face, whether they are students or not.

Zach Busby, 21, a senior at St. Edward’s and Holmes’ roommate, also does not have a car. He often chooses to pick up fast food from Taco Bell or McDonald’s rather than to lug groceries back to his apartment from Oltorf.

“It’s easier to justify living off $5 to $10 a day than walking two miles to the grocery store and carrying back bags,” Busby said. “When I buy groceries, it’s usually when one of my friends can drive me to H-E-B.”

Campus food is not a feasible option for Busby, who considers it to be too expensive and sometimes skips meals while on campus to avoid paying high prices.

The St. Edward’s area is considered a food desert in terms of a lack of transportation, but there are other ways of measuring food deserts.

Food Deserts in Austin

In Austin, 40 out of 218 census areas are classified as original food deserts by the USDA, meaning that 18 percent of census areas in Austin are considered to be low income and are located more than a mile away from a supermarket.

Much of East Austin, in comparison to the west side of I35, is a food desert. This is due largely in part to the lack of grocery stores in East Austin, as well as a lack of reliable public transportation system in the urban and rural parts of the area.

Food deserts regularly coincide with areas that are home to low-income communities and communities of color. These portions of the population often do not have enough opportunities to purchase healthy, affordable food, and because of this, people in these areas are more likely to suffer from diet-related diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

Sustainable Food Center

One organization that is dedicated to helping East Austin residents cultivate a healthy community by strengthening local access to fresh food is the Sustainable Food Center (SFC), which opened its first physical location on E. 17th Street on Sept. 24.

The non-profit hosts farmers’ markets in four different Austin locations, where they provide incentive programs for customers who receive federal food benefits. SFC also provides a free six-week healthy cooking class, La Cocina Alegre, or The Happy Kitchen.

Simone Benz, Community Outreach Coordinator at SFC, stresses the importance that her non-profit places on food education and civic outreach.

“We’re trying to put the power of the food back into the hands of the community,” Benz said.

One way that SFC is doing that is through a program called Grow Local, which encourages children and adults to grow their own food and share it with their neighbors. SFC supports participants by providing free gardening resources like seeds and compost as well as free gardening classes.

Benz grew up in South America and speaks Spanish every day with families in Austin to help them navigate through better food options. Benz worked with a single mother of three that felt embarrassed to ask for healthy foods at the grocery store because of the reactions she got from employees; either that they didn’t know where the food was located, or they gave her looks and asked why she wanted it.

“There’s a socio-economic assumption that these folks don’t want to eat healthily for whatever reason,” Benz said.

This trend of a lack of available fresh produce and meat for communities of color goes back to the 1960s when white, middle class families began to move from urban city centers to the suburbs, bringing the supermarkets with them. Now, white suburban neighborhoods still contain many more grocery stores than urban communities do, such as East Austin, and the stores that are in those communities are generally smaller and have less selection.

Benz has her own term for food deserts: food swamps, alluding to the large amount of greasy fast food, fattening snacks and sugary drinks that make up the majority of food options in chain restaurants and convenience stores in urban food deserts.

Living in a food desert, or swamp, is challenging, especially for those who do not have reliable transportation. But, Holmes has a positive outlook on his diet.

“I don’t find it to be too difficult to eat healthy in the St. Edward’s area, it’s just more of an effort,” Holmes said.