The People’s Slam Champ

Conquering assimilation through poetry

Saturday night, Alex Luu adorns himself in his traditional Chinese dress, a royal blue chènshān with intricate bronze dragons patterns. He strides on stage, and stops in front of the mic. His shirt is stark against the crimson curtain backdrops. I wonder, in the moments before he begins, if some audience members doubt how good his English will be.

“The letter my grandpa never gave my dad,” he begins.

For the next 190 seconds, Alex commands the stage, gesture by powerful gesture, note by gripping note. He’s not giving a speech; he’s spitting a poem. Because this is the Texas Grand Slam and Alex Luu, to the disapproval of his parents, is a slam poet. He is also skipping school, having travelled 1,488 miles from the University of Southern California for this competition. Little do they know, he is one poem away from $1,500.

Asian America

Asian-Americans are the quickest growing minority in the country, having shot up 72 percent, or 8.5 million people, between 2000 and 2015, according to the Pew Research Center.

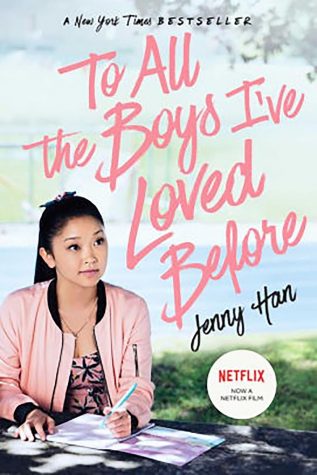

And though the recent massive success of “Crazy Rich Asians” is a landmark in the push for better representation as the first modern story in 25 years to feature an all Asian cast, it is by no means the beginning, or the end. Asian-Americans of all walks of storytelling – slam poetry, film, theater, literature, art – have been pushing to be heard and to fold their experiences into the American story on the local level long before the movie grossed $26 million during its opening weekend.

Wanna-be Rapper

“I got into poetry because I always wanted to be a rapper,” Luu reminisces, “but I could never rap on beat.”

But not for lack of trying. Before discovering slam, Alex would surf Youtube to find an instrumental beat, write some bars for it, and try to rap with as much rhythm as he could muster which, as he confirms, was not much.

Alex didn’t give up, though. He entered school talent shows and recited his lines without the instrumental, not realizing that these were his first attempts at spoken word.

It was third period, Mr. Slagle’s freshman English Honors class when he first encountered slam. Alex sat center classroom, a self-described “awkward, 5’ 5’’, chubby little Asian kid who wore big framed glasses and spoke with a prepubescent voice.”

“One day, Mr. Slagle was playing videos from HBO’s Def Poetry Jams in class. In my mind, it sorta seemed like rap but acapella.”

The quick paced, high-energy word play hooked him, not to mention its disregard for needing a beat which worked to Alex’s advantage. Witnessing Def Poetry Jams was, as he describes it, the “gateway art form” that led him to his greater slam poetry career.

But his verses would meander along in teenage angst themes of friend-zoning, bullying, and love for a little while. They wouldn’t come close to broaching his Asian-American stories until he was a sophomore in college, roughly four years later with “some sappy love anti-bullying pieces in between.”

Luu’s first slam poetry performance during San Gabriel High’s Anti-Bullying Month.

Bon Luoc

The Luu family is Chinese-Vietnamese-American, to add to the already complex identity of multi-nationhood. Driven out by war, Alex’s grandparents immigrated from Guangzhou, China, to Vietnam and then from Vietnam to California in the ’70s, driven out by war again.

“Being the son of immigrants and having grown up in America,” Alex says, “it’s definitely shaped my world, where I’d be the translator for my mom, where I’d have to explain certain American customs to my family and I’d have to explain a lot of my Asian culture and heritage to my friends.”

As a cultural middleman, Alex leads a double life, a very jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none feeling where, in an effort to escape choosing loyalties, he tried to compartmentalize his identities — a good Asian-American son at home and a fly-under-the-radar minority when out in the world.

“I’d be in a predominantly white, Christian school by day and at night I’d come back to family. I had an identity crisis like, what am I? Which community do I fit in?”

Alex chose to be American. “I had to do things to assimilate,” he said.

Things like throwing away his mother’s bon luoc as a kid because his playground bullies would call them worms and him a worm-eater; begging her instead for lunchables; being called Buddha Lover like a bad word; and finally, sacrificing himself on the sacrament of stereotypical Asian jokes to appease his tormentors.

Alex’s First

It’s easy to say, “Everyone needs a seat at the table,” without realizing many don’t even have the nifty IKEA instructions sheet to build a chair, let alone pull up a seat. Enter G Yamazawa, Japanese-American rapper, proud Durham, North Carolina boy, and Alex’s unrealizing instructions sheet.

“Seeing my representation in G, seeing that people vibe with him and felt emotional made me think, Wow, what are parts of my life that I can write about, can I be vulnerable with?”

G was Alex’s first. His first time seeing an Asian-American on stage, his first time hearing his own stories as a child of Asian immigrants being told, his first time hearing them applauded.

Much of G’s slam poetry, and later his music, centered around his experience as a Japanese-American son of immigrants, so for Alex, it was revolutionary to see an Asian hold a crowd with stories about his father’s accent, his mother’s cooking, his grandma’s stories.

The first piece that Alex would witness was G’s poem, “Dear Grandma,” an ode to his grandmother.

For the first time, Alex didn’t see himself choosing between Asian or American, but instead leaning into the power of the hyphen in Asian-American, realizing that, like him, it is a bridge between two entities. It forced him to reconcile with the Asian side of his identity which he’d worked so hard to repress.

“It was just dipping into this mindset that made me explore all that I had done wrong to myself, done wrong to my people, how much I had forsaken my culture, my heritage, my history.”

He began to write about his family, their food, their history. He studied Buddhism. He learned Chinese proverbs and mantras.

He got new shirts for slam.

“I would wear something called the chènshāns, which literally means long shirt,” Alex told me, diving into his backpack to show me not only what it looks like but how close-at-hand it stays.

He got the idea from seeing so many African-American poets wearing dashikis and traditional beads to stay in touch with their culture. He wanted to recreate this phenomenon of connecting to heritage through clothes for the Asian-American community.

Chènshāns are a traditional Chinese dress worn by men. “I would wear them everyday, just as a way to get in touch with my culture and feel how it feels to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors.”

Poetry was the medium that broke him out of the Asian-or-American dichotomy and poetry would be the tool with which he’d carve his own niche.

“I felt a sense of duty and a sense of responsibility to expose my own experiences to an audience and hopefully change some perspectives on how we live and what people think of us.”

The only problem is his family, the very subjects of his stories, don’t exactly approve of it.

Dad

Alex is in the trial-and-error process of progressing his parents towards acceptance of poetry as a viable path for him. It’s not that his family doesn’t appreciate it; they just don’t find it practical. And for parents who left a country to give their children a better life, practicality seems only necessary.

Learning his son had taken up slam poetry, Dad did the universally parental thing to do when your child comes home with a less-than-gainly new hobby: label it a phase.

“As I explain to them how important poetry is, how important art is, that this is something that is needed, that there is a market for it where people want to hear their own stories manifested on a stage, as much as I try to pitch that to them,” Alex takes a breath, “it’s not something they want to hear simply because they doubt my financial stability.”

So, Alex has made his own ways of getting through. If money’s the language his parents want to talk, he’s prepared to do one more job of translation.

Money Talks

Returning home to California from the Texas Grand Slam, Alex walks into his parents’ home to the sight of his father, arms crossed, lips pursed. He isn’t happy. Alex has skipped school for this poetry phase.

“It was one of those moments where you should get your ass whooped,” Alex recalls.

Before Mr. Luu has the chance to say anything, Alex reaches into his pocket, pulls out a check for $1,500, and slides it into his father’s hand. It’s his winnings from the competition. First place.

Alex Luu performed his piece, “The Letter My Grandpa Never Gave My Dad” at the Texas Grand Slam. Here, he performs it at Los Angeles’s All Def Poetry.

For the Culture

Saturday night, Alex Luu adorns himself in a vibrant yellow chènshāns with his grandma’s Buddha hanging around his neck. He’s got “jade for bones,” a “dynasty in his footsteps” as he strides onstage. It’s almost one year since his victory at the Texas Grand Slam and he’s gearing up to defend his title in a few days.

“I believe for us to create as artists is a divine thing,” Alex tells me. “For us to turn creativity into something solid for other people to acknowledge and love, that’s not normal. Everyone is in on the imagination that you make, and for you to be able to create that is powerful.”

His parents’ acceptance is an ebb and flow; some days they’ll be harsher about it, other days more relaxed. “It’s a process,” he says.

No matter what mood he finds his parents in, Alex wouldn’t trade poetry for anything.

“I never believed in myself and I never believed anyone would care for my Asian stories about my Asian background. (Poetry) helped me reclaim myself.”

I am Lilli Hime—English Writing and Rhetoric major and freelance writer at Hilltop Views. This is my senior year at St. Edward's University.

My role...