Second annual “Power to the People” discusses the intersection of race, incarceration

St. Edward’s University’s Black Student Alliance held its second annual “Power to the People” event, with this year’s focus on the intersection of race and incarceration. The main topic was “Justice for Us” and revolved around a panel of experts on the incarceration system.

“We wanted to create an event that educated the community around social issues,” BSA President, Alexis Reed, said.

This was the first “Power to the People” event with a focal point. Last year’s pilot, “Power to the People: Own Your Activism,” was created to help community members “take ownership of their activism.” This year’s event aimed to show people what it really means to dive into one issue, like incarceration.

“As soon as last year’s event ended, we started talking about planning for next year,” Erica Zamora, director of the Office of Student Diversity and Inclusion said. “(This event) came from an idea to try something new, for people to explore their own advocacy but also be exposed to new social issues that they may not have thought about before. BSA is one of our leaders on campus in terms of student advocacy, and it’s really fun to see them taking the lead and deciding what’s important and how to move it forward.”

Alexis Reed and BSA Vice President Courtney Reed helped warm up the audience with an anonymous online Q&A where they asked the audience questions like, “what are you looking forward to the most from Power to the People?” and “when you hear the terms race and incarceration, what thoughts arise?” For the first question, common responses were “allyship” and “staying up-to-date.” Answers to the second question were words like “for-profit prisons,” “war on drugs,” “wrongfully convicted” and “transitions from slavery to prison labor.”

After the icebreaker, President Fuentes introduced herself and spoke to the audience.

“Today, we focus on the courage to act after we hear from each other and learn from our differences,” Fuentes said. “I hope that after a day of spending together hearing concerns, different perspectives that affect our lives, we not only listen, but are the force – the power – that this society and the world needs. Students inspire me every day, force us to think better about how we can solve the injustices in this world.”

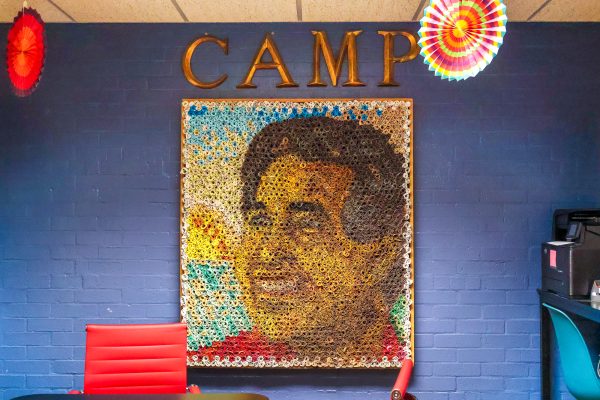

After Fuentes spoke,Natalie Beck Aguilera, an assistant professor in the sociology and social work department at St. Edward’s, introduced the moderator and panelists. Director of criminal justice at local nonprofit Texas Appleseed, Jennifer Carreon, moderated the event. Panelists included Chas Moore, the co-founder and executive director of Austin Justice Coalition; Katy Dalrymple, a current undergraduate social work student at St. Edward’s; Maggie Luna, a policy analyst and community outreach coordinator at Texas Center for Justice and Equity; Bill Wallace, founder and executive director of Tomorrow’s Promise Foundation; and Courtney Robinson, founder of Excellence and Advancement Foundation. Each panelist shared their personal experiences with incarceration and how these experiences drove them to dig deeper and combat the justice system.

“Some people get all of the chances before they end up there, but as a hispanic female in a predominantly white neighborhood, I was arrested just for being on campus,” Luna said.

“It’s not just oh she did something wrong, but your race, economic level, beauty laws. Even within the women’s prison, if you’re cute you get special opportunities; so I got harder, longer sentences. It has nothing to do with my achievement but as soon as an officer sees me, I am automatically the criminal.”

For each panelist, race had a role to play in their personal incarceration or a family member’s incarceration. After his arrest in Fort Bend County for second-degree robbery in high school, Moore was sentenced to eight years probation and spent two months in the county jail. Moore spent every weekend in the jail, was permitted to attend his graduation and then had to return to jail until his college orientation at the University of Texas at Austin. That same year, Moore, a Black man, witnessed his white peer receive no such sentence for a crime more punishable than second-degree robbery.

“You are free until convicted of a crime,” Robinson said. “This isn’t that Black people commit more crimes, but structure and law have been put in place to make the funnel so smooth that we don’t feel it happening. This isn’t an ‘oops’, but a structure and system.”

Each answer unveiled another layer in the complexities of the incarceration system in the United States, specifically in Texas. Wallace shared how prison labor was divided by race – indoor, factory jobs were often reserved for white inmates while field jobs, like harvesting and picking crops in the heat, were reserved for Black and other racial minority inmates. Luna explained how “pretty privilege,” where physically attractive people receive the upper hand, was something she started to notice while incarcerated. This privilege could get inmates better jobs and create better relationships on the inside.

According to panelists, Black and racial minority communities can face bias in the legal system before being incarcerated. Wallace explained how the discretion of officers changes the severity of punishment in the booking process and how it becomes a question of “what can I settle for?” for many. Moore’s sentencing was used as a prime example of this.

“As soon as an officer sees me, I’m automatically a criminal,” Luna said.

Luna, Wallace, Moore and Dalrymple shared the difficulties faced as a result of incarceration.

Luna is now rallying for legislation that puts “humanity in the prison” – essentially being more conscious of the basic needs for inmates – because of her experience in the Texas prison system. Dalrymple identified housing as being the hardest thing to acquire after serving time, as previously incarcerated people have to prove they are not a liability but an asset. Wallace explained how people are given a fifty-dollar check upon release from prison, which shocked many of the attendees.

All of the panelists imparted words of encouragement and advice to attendees before closing out the session. Many highlighted the importance of the audience being college students and the power that comes with being the next generation to impart change.

“Do not lose your imagination,” Moore said. “Keep dreaming because you are our leaders.”

Following the panel, remaining attendees gathered to debrief and discuss the panelists’ words. Small group discussions centered around civic privileges, like voting and the three-billion dollar prison industry.

“Power to the People” is expected to return next year, but it is unclear what the topic will be.

“Moving forward, the vision for (“Power to the People”) is always going to be around a social issue,” Alexis Reed said. “It’s always going to be around something that’s relevant to our community.”

Nina Martinez is a senior at St. Edward’s University, earning her Bachelor’s in Writing and Rhetoric. Martinez has reported and edited for Hilltop...

Melissa Gunning is graduating this December with a degree in psychology, minor in writing and rhetoric and certificate in evidence-based addiction counseling....