OURVIEW: News consumers must vet social media feeds for fake news

Where do our online personas end and our “real-world” personalities begin? Millennials practically live online; their sense of “reality” is derived from what they experience on social media. With few solid anchors or veritable filters, it’s difficult to navigate the mercurial virtual news world.

Facebook, Twitter and Instagram provide enough content for students to consume for hours and hours. So can it connect us to a larger world? It could. Does it? Researchers at Stanford University think not.

Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education conducted a study over the course of a year, involving nearly 8,000 students in elementary school through college across a dozen states, to assess their ability to discern real news sources from fake ones. The results were not encouraging.

According to researchers, more than 80 percent of middle schoolers thought that paid content, occasionally referred by certain mealy-mouthed public relations specialists as “native advertising,” was real news. NPR mentioned many students even pointed out that it was sponsored content, but still believed it constituted real journalism, suggesting they may have trouble with the definitions of “sponsored” or “content.”

Most high schoolers abruptly failed to verify the sources of photos.

College students failed to see the bias in social media posts from activists and advocacy groups.

All students had trouble discerning the difference between fake and real news sources, with 30 percent of students actually suggesting the fake news source seemed more trustworthy.

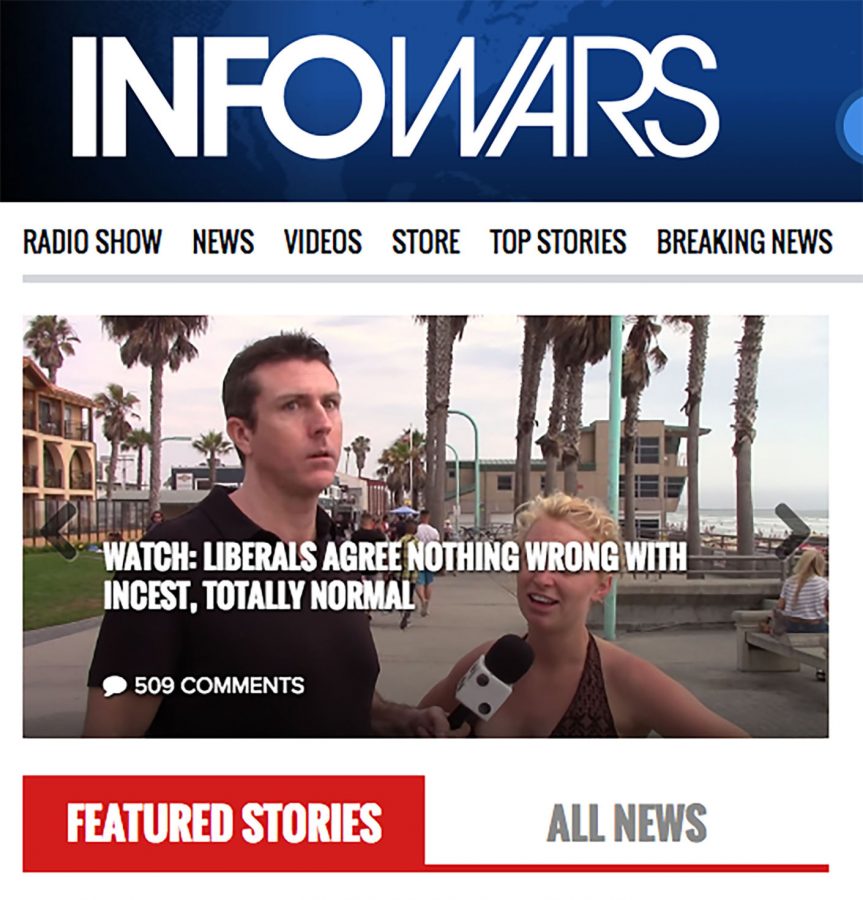

College students can’t tell the difference between mainstream news sources and fringe groups representing obscure or extreme views. I’m willing to bet that there are some professors who can’t either — or at least some that simply won’t.

Fake news appeals to our instinct for maintaining homeostasis. When we are presented with material that contradicts our views, beliefs and experiences, we are confronted with psychological stress regardless of the veracity of the source.

In order to avoid this discomfort, we’re wired to seek external means of returning to equilibrium. When we are cold, we could grab a blanket, turn up the heat, shiver or employ any number of methods to achieve a tolerable state. When it comes to our political beliefs, fake news functions like a blanket that shields us from the cold reality of factual reporting.

Even if we’re aware on some level the news we’re consuming isn’t true, our subconscious has ways of glossing over our distrustful sentiments by way of cognitive dissonance.

It’s the same mechanism that helps us justify all kinds of bad decisions. Even though we know that junk food is bad for us, we visit the vending machine anyway because cognitive dissonance pushes our minds to compensate for the gap between our feelings about the potential negative and positive outcomes of getting another Snickers bar.

On the one hand, we know we shouldn’t eat more candy because it will have negative effects on our well-being in the long term, but we know it will feel good immediately. And usually the promise of instant gratification and low blood sugar prevails: We eat the candy, we share the fake links.

It’s hard to outsmart processes that occur so far below the level of our conscious reasoning. So how can you avoid being suckered by Macedonian teenagers and Arizonan “entrepreneurs” making thousands of dollars a month by writing news a supermarket tabloid that writes about the Return of Bat-Boy would turn its nose up at?

By not being an idiot.

Read your news. And then look at the source. Is it an agency that can be called to the court for actionable falsehoods? Or is it a fly-by-night website whose only accountability is to its writers who only want money or notoriety?

And even on reputable news sources, is it an article, or is it an op-ed piece? Is it paid content? Are you going to be a sucker or are you going to be an informed consumer? Are you going to verify your sources? Statistically speaking, most of you will have had to write a paper or two by this time of year. You should be able to tell the difference between a good source and a bad one.

So instead of restricting it merely to academic papers, why not apply that skill to aspects of life that actually matter?