Tying mental illness to mass murderers only prevents honest conversation

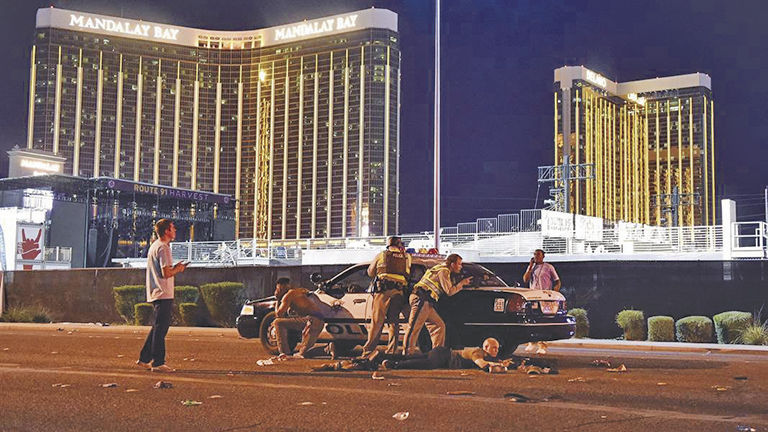

It has been over a week since the mass shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada, where 64-year-old Stephen Paddock killed 58 and injured over 500 in the worst mass shooting in modern United States history, and information is still trickling in. A repeating theme in reports is the framing of Paddock as a “mentally ill lone wolf,” which, while unsurprising, is still disappointing.

Describing white mass murderers as being mentally ill has been a long-standing American media tradition, but traditions are not always a good thing. In this case, tradition perpetuates the opportunity for intra-American terrorism, while also demonizing the mentally ill community. Two birds with one stone.

To elaborate, the narrative of a “mentally ill lone wolf” shooting hundreds of people creates the concept of an outlier. It says, most people who own guns don’t kill people. This was an exception to the rule. Guns don’t kill people, crazy people kill people. It’s a narrative that refuses to address the reality that America has a gun problem, and shifts the blame from a refusal to ineffective policy to random people with mental illness.

This is not to say that it ever proposes a comprehensive look at people suffering with mental illness.

People who frame mentally ill people this way seem to indicate that the mentally ill aren’t people per-se, but a vague concept which they can tack onto a tragedy to avoid a nuanced consideration of the issue.

There are solutions to the issue of mass shootings in America; there’s no need for us to be enduring as many gun-related deaths as we are. Other nations with comprehensive gun laws are able to, miraculously, exist with limited gun-related deaths. But rather than address that, many policy-makers choose to instead hide behind the second amendment, as if the two cannot somehow be reconciled.

Beyond avoiding the policies behind it, there’s an undeniably negative consequence for America’s mentally ill community. There’s already stigma regarding individuals afflicted with mental illness as being attention seeking or weak, and the pressure of these narratives emphasizes a sense of danger and fear with those who are mentally ill.

This is not a new concept, mind you, as the mentally ill have been portrayed as violent and scary since early fiction, and even relatively recent films such as “Fight Club,” “Psycho” or 2016’s “Split” prescribe to this notion.

This is then to be reflected in the public understanding of mental illness, creating a social and professional environment in which these individuals, who often need support, are unable to do so for fear of persecution. After all, who would want to have others associate them with people who are shown hurting others?

Talking about Paddock as anything other than what he is, a domestic terrorist, is dangerous on many fronts. It avoids the real issue of gun laws while also worsening the stigma for an already vulnerable group of American citizens. In an ideal situation we won’t have to worry about how future reports frame the next mass shooter.

But given the way it is currently going, there will be another mass shooting, and there will be more reports about how this “mentally ill lone wolf” was “quiet and unassuming” and the like. Mentally ill people will still suffer from stigma, citizens will still be at risk for being gunned down. Welcome to the United States.