10Ebola

On a gloomy Wednesday afternoon, as I made my way American Grammar, I ran into a friend I hadn’t seen all semester. He was walking with one of his friends I had seen around campus but had never spoken to.

With excitement, he ran towards me and flung his arm around me in a warm embrace. Realizing that, in our excitement, we had ignored his friend, he introduced us.

I asked her where she was from. She answered she was from Lubbock. She asked me where I was from. I told her that I am from Sierra Leone.

I saw a look of shock wash over her. I assumed it was because she had never heard of such a country. She asked me if she should be worried. I was, in all honesty, very confused.

I asked her what she meant, but my question was met with more questions from her.

She asked me when the last time I was there was. I was there two summers ago.

I stood with a look of absolute confusion. Noticing the expression on my face, she casually explained that with Ebola and everything going on, she’s shocked that I am here.

I put on a painful half smile and excused myself to class.

Her comment did something to me that I never thought could happen. It made me embarrassed of my African heritage.

Typically, when people ask me where I am from, I joyfully say that I am from Sierra Leone in West Africa, but after my encounter with this girl, things changed.

In the next couple of weeks following that incident, when people asked me where I am from, I told them I am from Houston.

Throughout the Ebola crisis, I worried about the impact that the outbreak would have on different aspects of African life such as economy, culture etc. What I never predicted was that those of us Africans living outside of Africa would face such stigmatization.

I have heard similar stories from my African friends and families all around Texas. My aunt, Gloria King-Hoff had a similar experience when she went to a county clerk’s office in Houston.

“The clerk realizes that I am an African, she freaks out and says ‘I hope you haven’t just come from Africa because a lot African people have been coming in here and I don’t want to get Ebola,’” she recounts in a Facebook post.

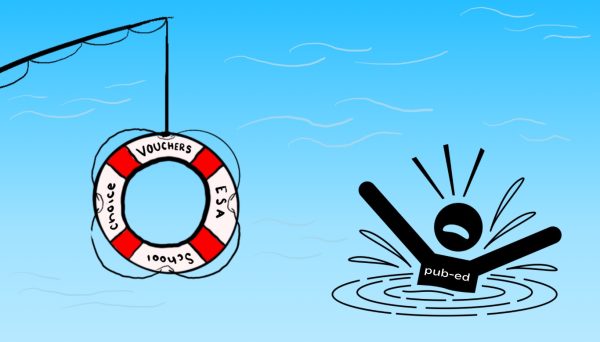

It is clear that these acts of stigmatization are fueled by pure ignorance; ignorance regarding how the disease is spread and who is at risk.

While it is evident that these stigmas do not come from a place of hate, it is still heartbreaking to know that even in America, the land of the brave and home of the free, we are allowing a terrible plague like Ebola to threaten the liberty and freedom that this nation was founded on.

We did not ask for this plague to befall our home, and at this time what we need is support. The kids in West Africa who have lost their parents, the parents that have lost their children, the communities that have been torn apart need support.

The millions of West Africans living abroad, worrying everyday if they will receive a phone call saying someone they love has died of Ebola, we need support. We do not deserve to be stigmatized and marginalized because of this woe that has unfortunately befallen us.

We are living in hope that this epidemic will come to an end. During the entirety of this Ebola crisis, the mantra of West Africans everywhere has been: This too shall pass.

We believe that Ebola will go. West Africa is full of strong, powerful fighters. Most of these countries have undergone ruthless civil wars and many West Africans have unbelievable horror stories to tell, but yet they have hope.

We believe that if we could get through some of the most brutal civil wars the world has ever seen, we can get through Ebola. But we would like to solicit the empathy of our friends all around the world.

We ask that you put yourselves in our shoes and try to imagine what we as a people are going through. We ask that you educate yourself on the virus and take precaution. But do so not at the expense of stigmatizing all of us Africans. We are Africans, not a virus.