Cultural foundations ground students in real world issues

Each week, we explore both sides of a current issue through opposing Viewpoints. The alternate editorial for this week’s Face Off can be found here: “CULF classes great in theory, needs major reconstruction.“

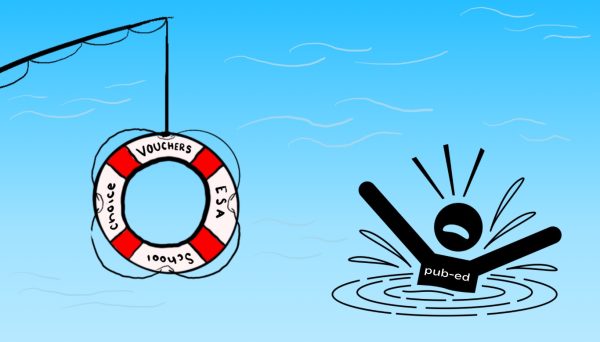

Odds are, you’re taking a course next semester with the much-dreaded cultural foundations (CULF) prefix. What is it about these mandatory courses that cause such a buzz around registration time?

For some students, it could be the fact that these classes frequently have nothing to do with their major or minor. It could also be that the classes are known to be associated with a heavy workload.

No matter the cause of our apprehension about CULF classes, one cannot negate the value they add to the liberal arts education St. Edward’s University students graduate with every year.

I recall a high school teacher warning my macroeconomics class that academics and professionals have become the victims of an “overspecialization epidemic”. For me, this infection manifested itself in goal to pursue the profession of cardiothoracic surgery.

At 16, I was prepared to take on a course of study nearly equivalent to the number of years I had been alive, which easily surpassed the number of years I had been coherent. I was desperate to be specialized in one tiny sliver of what the medical field had to offer.

Of course, I only possessed a tiny sliver of rationality as a high school student, and my interest has now solidified in politics.

Nevertheless, the will to specialize — and, by doing so, devoiding myself of history, language, business, entrepreneurship, art, so forth and so on — was strong, even at that young of an age. I took the perceived importance of specialization to heart.

With this in mind, is it any wonder that the university requires its bright-eyed and bushy-tailed freshman to sign up for courses like borderlands; religion, self and society; or religion and science?

Students who changed their major once or twice will likely testify that classes within the CULF curriculum can offer some direction in a person’s interests.

For those students who already decided on a major, CULF classes provide context to these studies and also serve to ground a person in real world issues beyond their major.

An economics major cannot weigh the pros and cons of free-market and state-led economies without broadly understanding how each system effects poverty and affluence.

A political science major cannot compare democratic and authoritarian regimes without knowing how each system influences the precious balance between freedom and equality.

A philosophy major cannot compare the theories of Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes and Adam Smith without knowing how people have fared under each of the systems these individuals endorsed.

CULF classes provide the historical testimony necessary to approach all these contrasts from a particular major’s perspective. CULF courses guide students’ understanding of what they learn by providing evidence, by making all the conjecturing and speculating real.

Follow Chris on Twitter @christopholiva