St. Edward’s tuition rising beyond reach

In his recent State of the Union address, President Barack Obama frequently made reference to the need to be globally competitive. In hopes of achieving this goal, Obama repeated that college should be within the reach of all American students. While the statement is comforting, the limited power of the federal government over educational institutions leads one to wonder how he plans to make college affordable.

By expanding Pell grants, offering a $10,000 tax credit and providing student loans through the Department of Education, the federal government has made repeated efforts to ensure that students are able to earn their degrees. These policies have helped to some extent, but the real impact on the average student is marginal at best.

Students in their fourth year at St. Edward’s have seen their annual tuition rise at an astounding rate—nearly 30 percent—since they were freshmen. Consider a mandated commuter meal plan, a technology fee, parking fees and the ballooning cost of on-campus living, and you have a list of expenses that few students can comprehend, let alone pay. The only expense that may have decreased for students is textbooks, but only because of the increased competition from alternative textbook providers.

St. Edward’s likes to note its generosity in financial aid, despite the fact that such generosity is only made necessary by the university’s insistence on increasing tuition. But some of that aid comes as loans, so students continue to rack up debt that they will have to pay later. Is this justifiable? Has the quality of education at St. Edward’s really increased 30 percent since 2007? As a degree becomes more necessary for competing in the job market, these price hikes are becoming more like extortion than a non-profit university’s attempt to offer a good education at market value.

Another factor in collegiate expenses is students’ performance in K-12, which has problems well beyond funding levels. Students that perform poorly in grade school have to work harder to catch up in college, making a fifth year and another $20,000+ bill almost inevitable.

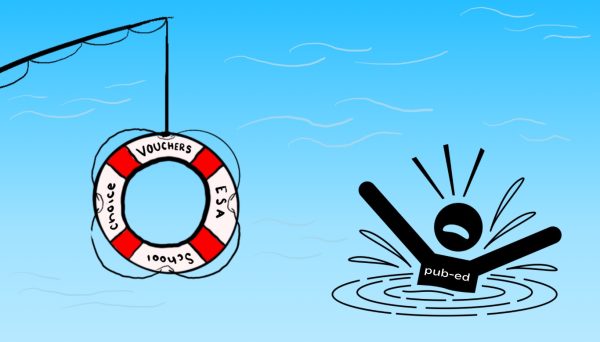

Facing cutbacks and consolidation, public schools across the state have had to make tough budget choices that will likely widen the education equality gap. Meanwhile, St. Edward’s is pricing itself outside of the range of many students, which could have devastating implications for the campus diversity in which it takes such pride.

As a private university, St. Edward’s won’t be immediately affected by the budget demands at the state or national level. Just across the river at the University of Texas, budget cuts have already been required, discussed and protested ad nauseum. Still, UT has built a well-connected institution that will weather the current storm. The voices of college students may be heard loudly now, but the next generation of college students will suffer the most.

In the 125 years since its founding, St. Edward’s, like all other colleges, went from being a place reserved for the elite to a necessary educational step that students must take to compete in a new economy. As a college degree becomes more common, St. Edward’s has become more exclusive, accepting fewer students. The university’s new emphasis on becoming an international institution bets on a need to help prepare for the future—but at what cost?

It is natural to want to look to policymakers, but a single solution to educational problems doesn’t exist—especially not at the national level, since education is primarily a state and local issue. As all levels of government manage growing budget deficits, it is becoming clear how little the government can do for students.

Instead they should look first to their universities, the very same institutions that beg them to solve problems critically and make a difference in the world.