‘Happy Hood Music’: A conversation with a determined rapper on the rise

Gianni Zorrilla / Hilltop Views

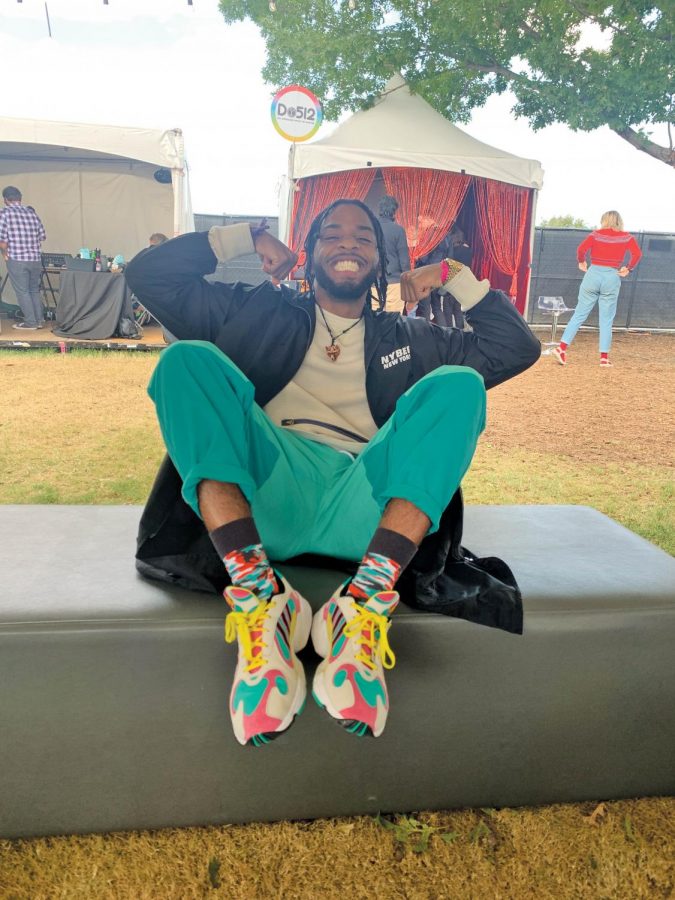

Armani White flexes his custom outfit in the ACL media lounge. White has worked and toured with artists like Troyboi, Big Sean, Vince Staples and James Blake.

When Armani White pulls up to the Austin City Limits Music Festival press lounge alongside his decked out entourage, his presence is impossible to ignore. He brings positive, seemingly inexhaustible energy into every space he enters. He’s the curator of what he calls “happy hood music,” after all.

White approaches, sporting bright teal track pants, colorful kicks and a long, stylish jacket fit for the uncharacteristically cold Austin afternoon. His enthusiasm is apparent (despite not having his pre-show ginger shots from Whole Foods), and he engages in friendly conversation almost immediately.

“I wanted to be a rapper my entire life,” White says. “Like even before it was cool to do it.”

The Philadelphia-born rapper started writing music when he was in the second grade.

He busts some moves in-between comments as fellow rapper Denzel Curry performs at the not-too-distant Honda Stage, then proceeds to discuss other influential artists.

“I heard this Eminem song called ‘Kill You,’ and I was like, ‘Yo, this s*** is tight,’” White says. Eminem was one of his major influences growing up along with James Brown and Ludacris. He recalls listening to these artists and thinking, “I wanna do that.” Before knowing any money was involved and before rap became a game everyone wanted to play, White was fueled by his passion and drive as a young boy in West Philly.

Philly is often shrouded by the shadow of New York. White calls it an “underdog city.” Because of this, he feels compelled to put everything into his work.

“I want to make sure I hold up that honor and hold up that coat of arms saying, ‘Hey, I could rap too,’” he says.

White began recording in middle school, thanks to a childhood friend who had a microphone in his bedroom. Before that, he would record on his phone, send it to his computer and try to match up beats. “It was terrible,” he says, his chin-length braids dangling as he shakes his head in laughter.

The sounds of a noticeably amateur, yet exciting ping pong game meld with festival background noise as we talk. White’s friends, who joined him on stage earlier in the day, play under a tent about 10 feet away from us. White periodically gestures toward the group, shouting them out, cracking a joke or asking a quick, playful question. They’re tight like that.

As White describes his music, it becomes more and more clear that his sound is an amalgamation of different cultures, passions and life experiences.

He moved around a lot, or “hopscotched around a lot of places,” as he puts it. Among the transition, he found himself. “That alone helped me lead myself into being aesthetically me,” he says.

White lost his father to prostate cancer in 2016. While the distress of loss caused a brief hiatus in his music, it also inspired him to create an album dedicated to his father’s life and its high points, which he is currently working on.

White likes to look at the bright side. He describes his music as “happy hood music,” a phrase he coined himself. It is a makeshift genre filled with major chords and upbeat sounds. However, the lyricism can be a little darker.

“The one thing that inspires me more than anything is pain,” he admits. “I like to try and take my pain and articulate that into music.” It could be expressed through trap music, struggle music, lively music — any kind, for that matter.

“For me, music is about really stretching the means of that genre and finding out what it is that you can do while still being considered a hip-hop artist,” White says. White continues to live up to his personal meanings of music and is clear about his ultimate goal within an ever-changing industry: “I wanna make something I love,” which he definitely stressed as he went 15 minutes over his scheduled interview time.

Hey everyone! My name is Gianni Zorrilla. I study communication and journalism and digital media here at St. Edward’s and am one of the Editors-in-Chief...