The U.S Department of Education announced Wednesday that it will eliminate $350 million in federal grants to Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), ending discretionary funding at St. Edward’s University, where more than half of the undergraduate population is Hispanic.

The move impacts 615 Hispanic-Serving Institutions nationwide as well as other minority serving institutions (MSI), including those serving large numbers of Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian students, Asian students and grants for predominantly Black and Native American-serving institutions not founded as historically black colleges or tribal colleges, as reported by the Chronicle of Higher Education on Wednesday.

“These designations and programs are more than labels — they represent lives changed, first-generation students supported and pathways created for futures once thought out of reach,” St. Edward’s University President Montserrat Fuentes said in a statement released to the campus community Thursday morning.

The statement continued: “The urgency is clear: More than half of our incoming students are Pell Grant recipients” and said the university is “actively seeking other avenues of support, including state partnerships and philanthropic investment.”

The DOE notified grant recipients Wednesday that existing discretionary awards will not be continued and no new grants will be awarded for fiscal year 2025.

The MSI announcement follows a federal lawsuit filed in June by the state of Tennessee and Students for Fair Admissions based in Virginia, challenging the constitutionality of HSI funding. The lawsuit gained momentum after the U.S. Justice Department said it will not defend the program.

Edward Blum, founder of Students for Fair Admissions, told Hilltop Views on Tuesday that “all under-resourced colleges should have the same funding from the U.S. government, regardless of the race or ethnicity of its student body.”

He cited Huston-Tillotson University, a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) located in Austin, saying it “should have access to the same resources as St. Edward’s University even though there are not very many Hispanics enrolled there.”

When asked if his organization will mount a legal challenge to HBCUs, Blum said “HBCUs are different and SFFA will not initiate a challenge.”

He then stated that, “HBCUs are legal because federal support is tied to historic designation (pre-Civil Rights Act) to educate black students and is now applied in a race-neutral manner.”

Blum did not respond to a request for further elaboration.

St. Edwards’ legacy as a Hispanic-Serving Institution

In 2023, St. Edward’s was awarded the Seal of Excelencia for its academic success, retention and graduation rates for Latino students. SEU was the only Catholic university, as well as first private university in Texas and second private university in the U.S, to receive what the university’s website describes as the “prestigious” and “distinguished” three-year certification.

Fuentes touted the designation and is quoted on the university website:

“Earning the Seal of Excelencia is a reaffirmation of the accountability St. Edward’s has to inspire our Hispanic and Latino students to pursue their academic goals and achieve them,” Fuentes said. “The Seal is a testament of our dedication to our students’ success, because they are our future.”

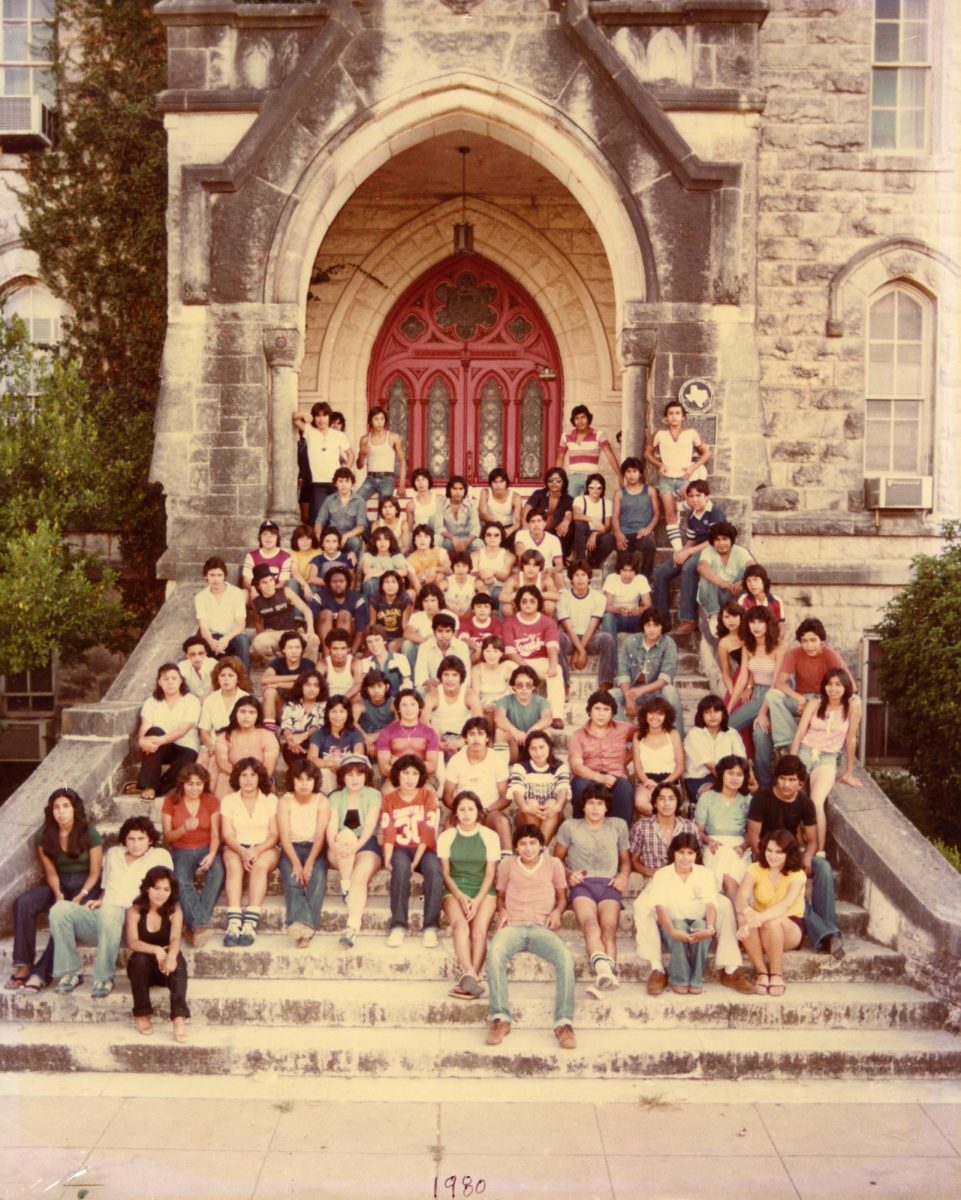

Before receiving the Seal and the federal HSI designation, St. Edward’s had been serving Hispanic students for decades. In 1958, the university established what was first called the Latin American Program, admitting students from Nicaragua, Guatemala and Mexico for English training.

According to “Saint Edward’s University: A Centennial History” by William Dunn, “American Hispanic” enrollment “rose steeply” in the 1970s and 1980s, reaching 452 students by 1983. The university also welcomed significant numbers of Mexican boarding students at its high school, which operated until 1967.

The current legal challenge comes as St. Edward’s continues to grapple with how best to reflect its diverse student population.

In 2022, the university renamed Doyle Hall as part of Strategic Plan 2027. The new name, Equity Hall, was intended to, “promote the critical work we do in support of diversity, equity, inclusion and justice daily,” an announcement to the campus community said at the time.

These efforts reflect findings from a 2021 report commissioned by the university’s President’s Task Force on Systematic Racism, which documented the broader historical context that led to targeted federal programs for Latino students, detailing “Juan Crow laws,” segregation laws specifically targeting Mexican Americans in Texas and systematic violence against ethnic Mexicans in the early 20th century.

What an HSI designation means

Hispanic-Serving Institutions are defined under federal law as colleges or universities where “at least 25 percent Hispanic students” comprise undergraduate enrollment. The designation traces back to the Higher Education Act of 1965, though Congress didn’t begin funding HSI programs until the 1990s after finding Latino students were attending college and graduating at far lower rates than white students.

According to the Office of Institutional Effectiveness and Planning 2024 Factbook, 56.1% of St. Edward’s undergraduates identify as Hispanic, well above the federal threshold. The case targets funding streams that have supported capacity-building programs, laboratory equipment, student services and faculty development at HSIs for nearly three decades.

Data from the factbook reveals the percentage of Hispanic students at St. Edward’s University’s increased from 25.4% in 2001 to 56.1% in 2024, with no year-over-year decreases. This sustained growth shows the university has evolved beyond the federal 25% HSI threshold, with Hispanic students now comprising a majority of undergraduates.

The Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU), based in San Antonio, has moved to intervene as a defendant in the lawsuit, contending that eliminating the program would harm institutions that educate over 5.6 million students.

“Cutting this funding strips away critical investments in under-resourced and first-generation students and will destabilize colleges in 29 states. This is not just a budget cut, it is an attack on equity in higher education,” said David Mendez, HACU’s interim CEO in a statement following Wednesday’s announcement.

Mendez emphasized that HSI funding “has never supported only Latino students.”

“These funds strengthen entire campuses, creating opportunities and resources that benefit all students, especially those pursuing STEM fields, as well as enhancing the communities where these colleges and universities are located,” he said.

What HSI status means to students and alumni

For many St. Edward’s students and alumni, the lawsuit represents more than a legal challenge to federal funding criteria.

Isabella Hernandez, a May 2025 psychology graduate and child of Venezuelan immigrants, said the issue “feels deeply personal.”

“It is deemed ‘unconstitutional’ to consider ethnicity in admissions, yet the system continues to disproportionately disadvantage certain communities,” Hernandez said.

Juan Diego Guerrero, a senior communications student, said the St. Edward’s HSI designation “makes it a lot more welcoming and inclusive for young adults with Hispanic backgrounds like myself.”

Though he has limited knowledge of the lawsuit, Guerrero emphasized that “creating an inclusive environment is very important in the transitional period between high school and college.”

For Myrka Moreno, a 2019 graduate and CAMP program alumna from the Rio Grande Valley, St. Edward’s Hispanic community proved essential to her college success. Coming from a predominantly Mexican area where no immediate family members had left for college, Moreno said the transition to Austin was “really scary, not just for me, but for my whole family.”

“A lot of what helped my mom see that it was the right move for me was that there was a huge Hispanic and Latino culture at St. Ed’s,” Moreno said. Through CAMP, she found “people who also spoke Spanish, or were in-between being a Hispanic-American or being Mexican-American.”

“Finding those people, like other people who looked like me, sounded like me and had similar experiences to me, was really comforting and validating,” she said. “I don’t think I could have finished or survived my college journey without” that community.

Hernandez said that since the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision ending affirmative action, “low-income students — particularly those from Hispanic communities — have felt its impact.”

She questioned how to reconcile these competing principles, adding that “this debate will remain unresolved until the Supreme Court sets clearer guidance.”

Joaquin • Sep 16, 2025 at 7:31 pm

The decision to cut HSI funding is not the attack on equity the article claims it to be but rather a long overdue correction to a system that was fundamentally unfair. Federal education dollars should be distributed based on need, not race. Yet HSI and similar programs funnel money to schools based on the ethnic makeup of their student bodies. That is not equity, that is racism disguised as progress. Low income white, Asian, or other non Hispanic students at struggling colleges are just as deserving of support as Hispanic students, yet this program excludes them simply because of skin color or ethnicity. The article romanticizes the designation as if it inherently makes a school more deserving, but in reality it bakes racial favoritism into federal policy and ignores the broader population of disadvantaged students. True fairness comes from funding institutions on the basis of economic hardship and under resourcing, not identity politics. Equity that picks winners and losers based on race is not equity at all, it is discrimination.